|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND |

|

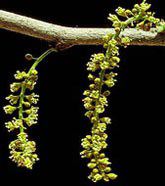

OUCH, HONEY! Autumn in temperate North America is a splendid time when crisp temperatures, blue skies, and Technicolor leaves make it a joy to be outside. From a distance many tree species at Hilton Pond Center bear hues that are nearly indescribable, but unique: the deep purple of the Sweetgum is quite unlike the brilliant yellow of the Tulip Poplar, and the orange-red of a mature Sugar Maple simply takes one's breath away. Indeed, fall colors can be distinctive, but in other seasons we identify trees using different clues: flowers in spring, leaf shape in summer, and bark or twigs in winter. This week when we accidentally backed into a tree trunk, we were abruptly and painfully reminded that--no matter what the season--some tree species can even be identified by touch. Ouch! Honeylocust!  Honeylocust is a native tree with a prickly reputation; its branches bear sharp, reddish-brown thorns (above), and the trunk may be so armored--sometimes, to our chagrin, at hip-height. Ouch! The tree's technical name, Gleditsia triacanthos, comes from the German botanist Gottlieb Gleditsch, and from Greek words for "three-spined" since new thorn growth often branches into threes. Interestingly, Honeylocust spines occur almost exclusively on trunks and low branches, which supports the hypothesis that their main function is to keep deer, rabbits, and other browsers from stripping bark or biting reachable twigs. Nothing like a super-sharp thorn in the lip to discourage nibbling. Ouch! Honeylocust seems to be a tree on the move. Historically, it grew in low riparian sites across the central U.S. but today can be found even in upland areas of the Atlantic coastal states. Although a moderately fast grower, the Honeylocust has dense, rather brittle wood that splits well and is sometimes used for fencing, pallets, and crating. Honeylocust is in the Fabaceae (Leguminosae)--the Legume Family--so it is actually a giant pea plant. About mid-May, its tiny yellow-green flowers (above left) appear prolifically on 2"-5" racemes but are obscured by foliage and gain little notice from the casual observer. The same cannot be said of pea pods that the flowers inevitably produce.

These foot-long leathery fruits--produced in huge numbers by mature Honeylocusts--often litter the ground beneath and provide an autumn bonanza for hungry squirrels, deer, fox, crows, and quail. From the outside, the purple-black pods show bumps (above) that correspond with individual peas within. The peas are protein-rich (up to 13% by weight), and the pulp that surrounds them may contain 40% carbohydrates. Peas and pulp are both edible and nutritious for humans; just be sure to lick your fingers to get the full taste and texture of the sweet, sticky goo inside the pod. Although most fruits fall from the Honeylocust by late November, a few twisted pods may hold tight through the winter, making it possible to identify the naked tree even from a distance. The longer the fruit goes uneaten by larger animals, the more likely it is to be attacked by small critters, and old pods are often riddled with insect holes; thus, One of Honeylocust's relatives in the Pea Family is Black Locust, Robinia pseudacacia, a fast-growing compound-leafed tree common along roadsides at higher elevations from Alabama northward to Pennsylvania. Black Locust also produces pods, but the fruit is flat and dry and inedible for humans. The main trunk of young Honeylocusts is smooth and gray and usually coated with pale green crustose and foliose lichens. In older trees, the thin bark curls back to produce long cracks that provide shelter for everything from spiders to beetles to lizards, and that give birds such as nuthatches and chickadees plentiful places in which to hide sunflower seeds from the backyard feeder. We really appreciate Honeylocust trees and are pleased to have some nice specimens at Hilton Pond Center. Like them or not, however, we learned our lesson this week--Ouch!--so the thorn-bearing Honeylocust is one species for which we are not going to demonstrate our tree-hugger reputation. OUCH! If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help Support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! Honeylocust flower photo courtesy Virginia Tech. |

Occasionally, individual Honeylocusts produce no spines at all, and scions from these trees have been cultivated and sold commercially to property owners who would rather avoid puncture wounds inflicted by their landscape plants. Ouch! Other folks have taken advantage of Honeylocust's stout thorns, including Civil War soldiers who reportedly used them to keep their uniforms together when metal pins were scarce. We assume the troops used the thorns on coats and jackets but not on trousers. Ouch!

Occasionally, individual Honeylocusts produce no spines at all, and scions from these trees have been cultivated and sold commercially to property owners who would rather avoid puncture wounds inflicted by their landscape plants. Ouch! Other folks have taken advantage of Honeylocust's stout thorns, including Civil War soldiers who reportedly used them to keep their uniforms together when metal pins were scarce. We assume the troops used the thorns on coats and jackets but not on trousers. Ouch! Its foot-long leaves are compound-- doubly (silhouette, above right) or sometimes singly--with each oval, pale-green sub-leaflet up to half an inch in length. Honeylocust is one of the few trees that produces no discernible terminal buds at the tips of its branches. The species is definitely sun-loving; if overshadowed by taller trees in the woods, it limps along for years but is quick to take advantage of any opening in the canopy due to treefall. In a good spot a 120-year-old champion Honeylocust can produce a trunk six feet in diameter, with top branches reaching 140 feet. Honeylocust is also a tree with a high tolerance for salt and air pollution, making it a likely survivor along industrial streets where de-icing compounds and smokestack emissions may kill other ornamentals.

Its foot-long leaves are compound-- doubly (silhouette, above right) or sometimes singly--with each oval, pale-green sub-leaflet up to half an inch in length. Honeylocust is one of the few trees that produces no discernible terminal buds at the tips of its branches. The species is definitely sun-loving; if overshadowed by taller trees in the woods, it limps along for years but is quick to take advantage of any opening in the canopy due to treefall. In a good spot a 120-year-old champion Honeylocust can produce a trunk six feet in diameter, with top branches reaching 140 feet. Honeylocust is also a tree with a high tolerance for salt and air pollution, making it a likely survivor along industrial streets where de-icing compounds and smokestack emissions may kill other ornamentals.

if you're going to dine on these wild delicacies you should harvest them shortly after they drop.

if you're going to dine on these wild delicacies you should harvest them shortly after they drop.