|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

|

|

COMMON RAGWEED:

STEALTHY SNEEZEMAKER

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The photo above, taken roadside not far from Hilton Pond Center, includes only two plant species in the foreground. One is bright yellow and showy, the other pale green and not particularly noticeable as one rides down the highway in mid-September. Both plants are a sure sign it's autumn, that time of year when summer finally loosens its molten grip and nature makes one last burst of activity before settling down for the long, cold winter. Fall wildflowers bloom profusely as human beings go out to romp and play, but at this time of year many of us outdoorsy humans fall victim to dreaded fall hayfever--so much so that puffy eyes, runny noses, hacking coughs, and wheezy sneezes are just as much a sign of autumn as changing colors and the honking of migrant Canada Geese. So what causes autumn hay fever? Why it must be that bright yellow flower along the road. Wrong! The yellow inflorescence is one of the Goldenrods, magnificent native wildflowers that get the blame for hay fever when, in reality, it's plain old Common Ragweed that hides in Goldenrod's shadow and is the REAL stealthy sneezemaker.

Yes, Goldenrod gets a bum rap each fall from those not in the know, folks who see its showy yellow flower clusters and simply assume it is to blame for clouds of pollen that make us sneeze. Nothing could be further from the truth, for Goldenrod makes sticky pollen that must be transported by insects, while every healthy Common Ragweed plant spews tens of thousands of dry pollen grains that are lofted by autumn breezes and into human eyes and mouths and noses. Some sources claim 90% of hay fever cases in the U.S. are caused not by hay or other grasses but by Common Ragweed, which may yield up to a billion pollen grains per plant! It's understandable people are fooled by the juxtaposition of colorful goldenrods and obscure ragweed. Even old Carolus Linnaeus--the early botanist and taxonomist who named new plants from specimens sent to him in Sweden--seemed unaware Common Ragweed is responsible for many fall allergies in America. In fact, he dubbed this sneeze-producing plant Ambrosia artemisiifolia, which to us hay fever victims is some sort of cruelty joke; in mythology, "ambrosia" was the "food of the gods" that granted immortality, and we know Common Ragweed is anything but. The plant's species epithet is a little more acceptable because Artemis--twin sister of Apollo--was Greek goddess of the hunt, and the leaf of Common Ragweed (above and below) resembles an ornate arrowhead she might have used to slay a stag. Less poetically, some folks say the term "ragweed" comes from raggedy edges of the leaf, but outdoorsman Jim Casada tells us ragweed actually "got its name from the fact that it occasioned the necessity of constantly going to one's handkerchief, colloquially called a "rag.'"

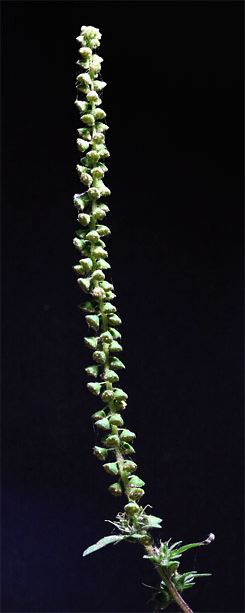

Like various Goldenrod species, Common Ragweed is a native plant that gets to about three feet or so in height and these days grows almost everywhere in the contiguous states--plus Hawaii. Our Common Ragweed is also pestiferous for farmers, lowering corn and soybean yields by about 30%. We must admit that despite its agricultural unfriendliness and dastardly pollen production, Common Ragweed is actually a pretty interesting plant--especially when its parts are viewed at higher magnification than our watery eyes normally see. All the ragweeds--41 species worldwide--are monoecious, i.e., they produce male and female flowers separately but on the same plant. Branching from the plant's main stem is a long graceful spike (above right) that bears as many as a hundred male flowers. These greenish-yellow staminate blossoms, less than an eighth of an inch in diameter, hang downward like little bells that dump pollen as they ripen. Female flowers--obscure and whitish-green--are positioned on leaf axils at the base of the spike (at bottom in photo above right)--exactly where they can be bombarded by dusty pollen from the many male flowers dangling above.

A closer view of a Common Ragweed spike shows each staminate flower attached to a slightly hairy stem by a thin green petiole. The spike in the photo above is festooned by delicate webs from what we first thought must be tiny spiders--some of whose sticky silk was contaminated by grains of ragweed pollen. Turns out the silk came from an unexpected source we'll mention later.

In photomacrographic analysis (above), the male flower of Common Ragweed is a jumble of minute parts. Each flower has five lobes and five stamens on which the pollen actually forms. Note there isn't a corolla (i.e., no sepals or petals) associated with ragweed's male flowers. For several reasons--including the disc-like shape of the male flower--ragweeds are classified in the Sunflower Family (Asteraceae), even though they lack the typical star-like shape.

The magnified quarter-inch-long female flower (above) looks a little less complex than the male, although nothing in nature is ever as simple as it appears. Again, the corolla is absent, with only a forked, purplish eighth-inch-long pistil emanating from an ovary and surrounded by a ribbed white tube (the calyx) and several green bracts. In the photo above, several dozen microscopic pollen grains are already attached to one upward-pointing fork of the pistil. From there the successful pollen grain grows a pollen tube down to the ovary where fertilization actually occurs. Each ovary thus fertilized makes a single reddish-brown achene--a naked, dry seed that lies in the soil until sprouting the following year.

Common Ragweed has a shallow taproot (above)--easily demonstrated by an upward tug on the main stem that almost always causes the whole plant to pop right out of the earth. This is good news for homeowners who can roam their property plucking ragweed in mid-summer before it has time to make pollen. The other good news is Common Ragweed is an annual, so each plant is destined to die at the end of the current growing season. (Inasmuch as Common Ragweed is a native plant, we feel somewhat guilty decrying it so vehemently, but it's the best we can do right now as our eyes water so much we can barely see our computer screen.)

After finishing up our photos of Common Ragweed's various parts, we went back and looked more closely at the webs draped across the leaves and flowers. There we discovered the little critters that formed the silken strands mentioned previously: Bright red spider mites with eight legs and slightly hairy egg-shaped bodies. These miniature arachnids are barely visible to the naked eye but showed up nicely through our 5x macro lens. Each mite is only 1/50th of an inch long, so in most Web browsers they should appear about 50 times life size in the photo above. We've often observed these tiny mites on other flora and never really appreciated them, but now we do. That's because spider mites are plant suckers, and they're obviously sucking juices from Common Ragweed. As far as we're concerned, any organism that diminishes ragweed's viability and pollen production is a friend of hay fever sufferers at Hilton Pond and elsewhere--whether or not folks realize it's stealthy Common Ragweed and not showy Goldenrod that's responsible for so many autumn allergies. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT: Barry OConnor, curator and professor for the Museum of Zoology at University of Michigan, suggests the red mites we found on Common Ragweed might be Strawberry Spider Mites, Tetranychus turkestani, a "polyxenous species [having no specific host plant] with almost cosmopolitan distribution" and the "only tetranychid [web-spining mite] reported from this host plant in the U.S. Barry says our ragweed mites could also be the "red form of T. urticae, the Two-spotted Spider Mite, which has been recorded from Ambrosia spp. and hundreds of other plants." We didn't mention we did find some green mites on the ragweed, each of which had two dark spots and could be T. urticae. These particular arachnids were even smaller than the red ones and moved too fast to capture with our macro lens. We note that identification of a mite to species often requires microscopic analysis of the male's reproductive structures.

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you ever shop on-line, you may be interested in becoming a member of iGive, through which nearly 700 on-line stores from Barnes and Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

Week One of our annual

Week One of our annual

Unfortunately for others, Common Ragweed was introduced accidentally to numerous overseas locations where it has become an invasive plant. In Hungary, for example, it is now reported to be the most common weed on old farms. In this country Common Ragweed is probably far more plentiful today than before European settlement, favoring sunny, open areas that increased dramatically with the loss of forest land.

Unfortunately for others, Common Ragweed was introduced accidentally to numerous overseas locations where it has become an invasive plant. In Hungary, for example, it is now reported to be the most common weed on old farms. In this country Common Ragweed is probably far more plentiful today than before European settlement, favoring sunny, open areas that increased dramatically with the loss of forest land.

Please report your

Please report your